|

Here's a narrative submitted by Bonanza Owner Ed L. of Texas to remind us all of the WWII B17 operating environment.

WARNING: GRAPHIC IMAGES:

See

this waist gunner in a B-17, flying at 28,000 feet? It’s -42 degrees

below zero heading for -60 below and his fingers will start to freeze in

one minute if unprotected! And if his M2 .50 jams, or needs to have a

new ammo belt, to continue to protect his segment of the bomber’s

defensive “box”, he WILL have to take off those gloves, and he WILL lose

the tips of his fingers, guaranteed. And if this young man, aprox. 20

years old, ever gets back home to Yourtown, USA…he won't have the tips

of his fingers and all of his toes.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-55f06e6d9cbdd98ae4263011a2bd9674-lq>

“Deep

frostbite (the most severe kind) means that all the layers of your skin

and the tissues beneath it have frozen significantly. When this

happens, your skin turns white or a bluish gray, and is numb to feelings

of cold or pain. It may be stiff and rubbery when touched, and your

joints and muscles may have difficulty working. After rewarming the

skin, fluid-filled blisters may appear within 24-48 hours, and the

damaged skin will turn black..”-Healthpartners

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-a3a5dae4b37725df0f168cc095d30c9e-lq>

“Severe

frostbite has longer-term affects and requires immediate medical

attention – sometimes involving hospitalization. In the most critical

cases, tissues are seriously damaged and amputation may be needed if

blood flow to the skin is permanently blocked. In other instances of

severe frostbite, patients may avoid amputation, but experience lifelong

numbness in the affected areas.”-Healthpartners.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-3635e11dde2afb20f2af405712cb104e-lq>

My

mom’s cousin, Fritz, from southern Minnesota, was the pilot of a B-24

in the ETO, and flew 25 missions…he came home missing several finger

tips and toes, not to flak, but to frostbite.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-58fae313a37b3ce3418134654e6a5ff9-lq>

(Above:

Famous photo from Life, Sept 1943. of some B-17 waist gunners. You can

see the electrical wires coming down powering their electrically heated

clothes and the oxygen tubes plugged in to the wall. Exposed flesh

freezes in a matter of mere minutes. Toes were esp. hard to keep warm,

and Fritz talked about the agony of just sitting there in the pilots

seat, his feet on the controls, unable to even stamp his feet as the

rest of the crew constantly did.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-7fd4dbead792c32bc7f2e42a99ad9094-lq>

(Above: Click for BIG cool image.)

One

of the biggest problems at that high altitude was oxygen. Over 12,200

feet and humans black out within a minute (this is not actually true,

one would likely be on the edge of hypoxia but certainly at 24,000'

things could go dark).

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-16e1a5c20d19d4d0768eae2b258dd189-lq>

Bomber

missions to Germany from England were often 8–10 hours long and the

planes were unheated and open to the outside air as the pictures

shows…and just imagine how hard it is to complete tasks in that

uncomfortable clothing — from the mask to the boots.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-4b7f990638cd678be5af8f7e1934cd46-lq>

The

crew wore electrically heated suits and heavy gloves that provided some

protection against temperatures that could dip to -60 degrees below

zero…but often short-circuited. Once above 10,000 feet they donned

oxygen masks as the bombers continued to climb to their operational

level that could be as high as 29,000–32,000 feet. Approaching the

target, each crew member would additionally don a 32-pound flak suit and

a steel helmet designed to protect against anti-aircraft fire.

Parachutes were too bulky to be worn all the time, but crewmen did wear a

harness that allowed them to quickly clip on their parachute when

needed…(but, oh, yeah, about that parachute: Bomber crewmen weren’t

trained to jump out of airplanes with parachute. They were simply given

instructions.)

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-e350bab2ab4d61a57892afc8f509a4f3-lq>

(Above:

As the first US bomber to have a pressurized cabin (and it wasn’t

sealed well, frankly,) was the B-29, crews risked all sorts of oxygen

depredation issues: hypoxia, altitude and decompression sickness, and

baro-trauma and that risk was high and dangerous, and all the bomber

crews got was an oxygen mask…that often didn't work, or froze up.

See those flak vests developed in ‘43? 32 easy pounds.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-ed158ce6f00726f02aa572b1be6e6f70-lq>

And

the tradition of wearing the silk scarf started from pilots in World

War I but it’s more than just for fancy fashion purposes. Its main

practical use was for protecting your neck against the wool material of

the uniform which will likely cause blisters.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-cb5c7aee6cc57fed12af7091e14d0a25-lq>

And

yet, again, imagine trying to move around in all that gear? Kneeling,

ducking, trying to shoot at the German fighters coming in at 200 mph

faster than you shooting 20–30mm HE cannon shells at you?

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-13251dbef373189a5f14297b9c4b2cb4-lq>

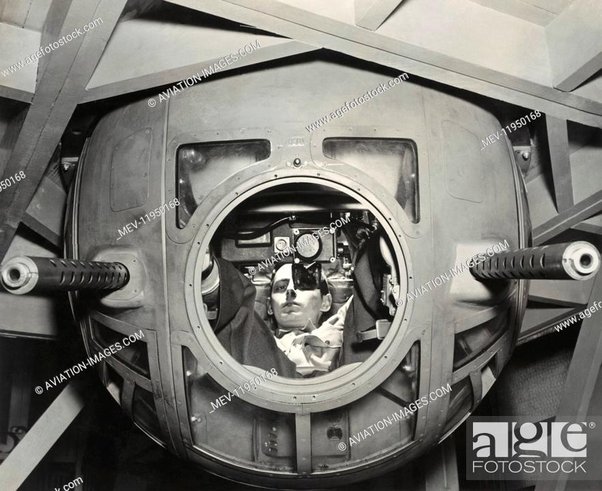

(Above:

One of the special features of the Ball Turret Gunner was extra

cold…hanging down in the 200 mph air stream at those high altitudes, and

that turret, though well-built, wasn’t “hermetically sealed”…it was

very drafty and extra cold. A miserable crew position, not to mention

lonely.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-8e1998edd7f77f28eb2ebacf00da6df8-lq>

(Above: Looking straight at the cockpit and looking up at the Top Gunner’s position.)

Prior

to 1944, a crewman's tour of duty was set at 25 missions…but that

number was almost statistically impossible in the ETO. Your chances of

completing all 25 missions, at least unscathed, were pretty much slim to

none. The Germans really dialed in shooting bombers out of the sky with

their sophisticated FLAK systems and method. The famed bomber “The

Memphis Belle” was the first to met this goal.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-1f0f7cf2615e94cba51309e741d311da-lq>

(Fun

Fact: During a “Memphis Belle” mission, the 91st Bomb Group unknowingly

blew up an entire cellar of cognac. They only found out later, and they

were distraught. Why is this significant? Well…Ok, it’s not. Just a lot

of wasted booze blown up.) As a measure of the hazards they would

encounter, it is estimated that the average B-17 crewman had only a one

in four chance of actually completing his tour of duty.

(Fun

Fact: Did you know that American pilots were required to take flash

photographs after dropping their bombs otherwise, it might not be

included in the required number of missions for a single tour!)

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-e75987fd4b2247d6ab2f60d59f8d6427-lq>

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-4ff68848aa8835cdfb8ddf5e9c7f107a-lq>

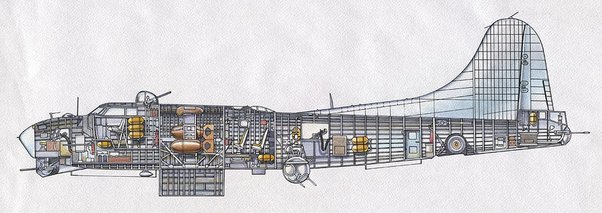

(Above:

Great illustration of a B-17F, showing the bright yellow portable

oxygen canisters crew members needed whentheyb disconnected to the main

oxygen lines to move about the ship, and many more aspects of a B-17

that kept the crew alive at 30,000 feet,)

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-35bbbdee9687ac76c0456c800729abde-lq>

(Above: The armour plate on a B-17.)

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-522a8f29653051f100f6d09f5c2e428d-lq>

(Above: Here’s some of a crew’s protective clothing.)

And

your legs (lower extremities) were the most likely part to get hit,

followed by your arms, (upper extremities) and your head.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-10cec3c26110446f75334dd5e612f957-lq>

(German flak was very good, as they had a loooot of practice.)

How old were they? Just kids, 19–20.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-d96d135876a76f91411564216132fb43-lq>

The

co-pilot was tasked with contacting all the other crew members every 15

minutes once they enter enemy territory. He needed to ensure that ALL

of them responded because otherwise it could/would be a sign that their

oxygen mask had frozen and they were dead or dying.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-827fc27455307fd53c11f2446e4a5753-lq>

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-9037e46c870ec163258cd1bd7449c94d-lq>

"I'm sorry, sir, I've been hit..."

Here’s the actually story of one B-17 crew member:

Joseph

Hallock was a 22-year-old First LT serving as the bombardier aboard

"Ginger" a B-17 flying out of its base north of London. Hallock dropped

out of college to enlist in the Army Air Force in June 1942. After

training as a bombardier, he arrived in England in November 1943 and

began his combat career on the last day of the year:

"My

first raid was on December thirty-first, over Ludwigshaven. Naturally,

not knowing what it was going to be like, I didn't feel scared. A little

sick, maybe, but not scared. That comes later, when you begin to

understand what your chances of survival are. Once we'd crossed into

Germany, we spotted some flak, but it was a good long distance below us

and looked pretty and not dangerous: different-colored puffs making a

soft, cushiony-looking pattern under our plane. A bombardier sits right

in the plexiglas nose of a Fort, so he sees everything neatly laid out

in front of him, like a living-room rug. It seemed to me at first that

I'd simply moved in on a wonderful show..' I got over feeling sick,

there was so much to watch.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-9781591dbedf222b58acebc33e59e9e1-lq>

“We

made our run over the target, got our bombs away, and apparently did a

good job. Maybe it was the auto-pilot and bomb sight that saw to that,

but I'm sure I was cool enough on that first raid to do my job without

thinking too much about it. Then, on the way home, some Focke-Wulfs

showed up, armed with rockets, and I saw three B-I7s in the different

groups around us suddenly blow up and drop through the sky. Just simply

blow up and drop through the sky. Nowadays, if you come across something

awful happening, you always think, 'My God, it's just like a movie,'

and that's what I thought. I had a feeling that the planes weren't

really falling and burning, the men inside them weren't really dying,

and everything would turn out happily in the end. Then, very quietly

through the interphone, our tail gunner said, 'I'm sorry, sir, I've been

hit.'

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-5a01f185704a072fabf58cc4515e1678-lq>

“I

crawled back to him and found that he'd been wounded in the side of the

head - not deeply but enough so he was bleeding pretty bad. Also, he'd

got a lot of the plexiglas dust from his shattered turret in his eyes,

so he was, at least for the time being, blind.Though he was blind, he

was still able to use his hands, and I ordered him to fire his guns

whenever he heard from me. I figured that a few bursts every so often

from his fifties would keep the Germans off our tail, and I also figured

that it would give the kid something to think about besides the fact

that he'd been hit. When I got back to the nose, the pilot told me that

our No. 4 engine had been shot out. Gradually we lost our place in the

formation and flew nearly alone over France. That's about the most

dangerous thing that can happen to a lame Fort, but the German fighters

had luckily given up and we skimmed over the top of the flak all the way

to the Channel."

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-50184075d386290a55b1b6f78543ab14-lq>

“In

early 1944 the number of missions required to complete his tour of duty

was extended from 25 to 30. This meant that Lt. Hallock and his

buddies, each of whom had been counting down each mission, now had five

additional to fly. We pick up his story as he begins his 27th (and

worst) mission:

"We

had a feeling, though, that this Augsburg show was bound to be tough,

and it was. We made our runs and got off our bombs in the midst of one

hell of a dogfight. Our group leader was shot down and about a hundred

and fifty or two hundred German fighters swarmed over us as we headed

for home. Then, screaming in from someplace, a twenty millimeter cannon

shell exploded in the nose of our Fort. It shattered the plexiglas,

broke my interphone and oxygen connections, and a fragment of it cut

through my heated suit and flak suit. I could feel it burning into my

right shoulder and arm. My first reaction was to disconnect my heated

suit. I had some idea that I might get electrocuted if I didn't.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-c70577348b8314c4dbcaf0d5966bf64d-lq>

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-8b1b815009fe56a8bc2e93e2bbc1face-lq>

“I

crawled back in the plane, wondering if anyone else needed first aid.. I

couldn't communicate with them, you see, with my phone dead. I found

that two shells had hit in the waist of the plane, exploding the

cartridge belts stored there, and that one waist gunner had been hit in

the forehead and the other in the jugular vein. I thought, 'I'm wounded,

but I'm the only man on the ship who can do this job right.' I placed

my finger against the gunner's jugular vein, applied pressure bandages,

and injected morphine into him. Then I sprinkled the other man's wound

with sulfa powder. We had no plasma aboard, so there wasn't much of

anything else I could do. When I told the pilot that my head set had

been blown off, the tail gunner thought he'd heard someone say that my

head had been blown off, and he yelled that he wanted to jump. The pilot

assured him that I was only wounded. Then I crawled back to the nose of

the ship to handle my gun, fussing with my wounds when I could and

making use of an emergency bottle of oxygen.

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-0da22c29201b424e8722119077c05111-lq>

“The

German fighters chased us for about forty-five minutes. They came so

close that I could see the pilots' faces, and I fired so fast that my

gun jammed. I went back to the left nose gun and fired that gun till it

jammed. By that time we'd fallen behind the rest of the group, but the

Germans were beginning to slack off. It was turning into a question of

whether we could sneak home without having to bailout. The plane was

pretty well shot up and the whole oxygen system had been cut to pieces.

The pilot told us we had the choice of trying to get back to England,

which would be next to impossible, or of flying to Switzerland and being

interned, which would be fairly easy. He asked us what we wanted to do.

I would have voted for Switzerland, but I was so busy handing out

bottles of oxygen that before I had a chance to say anything the other

men said, 'What the hell, let's try for England.' After a while, with

the emergency oxygen running out, we had to come down to ten thousand

feet, which is dangerously low. We saw four fighters dead ahead of us,

somewhere over France, and we thought we were licked. After a minute or

two we discovered that they were P-47s, more beautiful than any woman

who ever lived. I said, 'I think now's the time for a short prayer, men.

Thanks, God, for what you've done for us.'"

<https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-8f80f7311dd5b7af4b3a0bfee157a9b0-lq>

“The

twenty-eighth [mission]was on Berlin, and I was scared damn near to

death. It was getting close to the end and my luck was bound to be

running out faster and faster. The raid wasn't too bad, though, and we

got back safe. The twenty-ninth mission was to Thionville, in France,

and all I thought about on that mission was 'One more, one more, one

more.' My last mission was to Saarbriicken. One of the waist gunners was

new, a young kid like the kid I'd been six months before. He wasn't a

bit scared - just cocky and excited. Over Saarbriicken he was wounded in

the foot by a shell, and I had to give him first aid. He acted more

surprised than hurt. He had a look on his face like a child who's been

cheated by grownups.

“That was only the beginning for him, but it was the end for me."

|